Zack Kushner: “The Limits of Attraction”

Toru had always been exceptionally dense.

He was born like a slick cannonball. Coming out, he bruised the obstetrician’s fingers and crashed to the floor, cracking tiles. Despite measuring a reasonable nineteen and a half inches, Toru weighed a hundred and six pounds, three ounces.

Mom and Dad did not let their son’s unusual density disrupt their joy. They named him Tautoru, after his grandpa. The hospital just called him an insurance risk. Nobody felt too generous back then, even before the Sun went on the fritz.

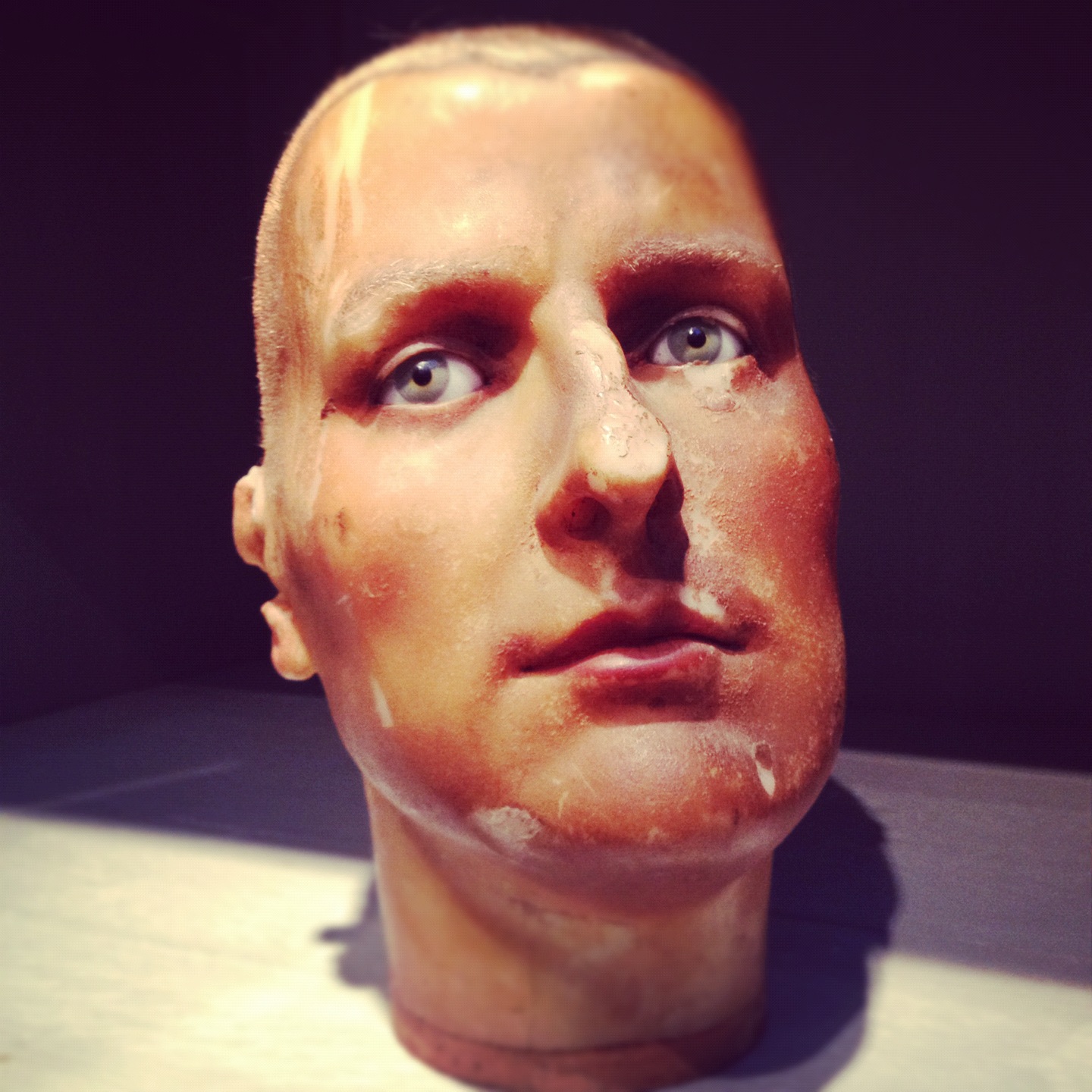

Doctors and scientists and carnival barkers ran endless tests on infant Toru. He grew up glimpsing scans of his skull and images of his guts, all marked up with that inscrutable doctor scrawl. Once they chiseled bits of his skin off and huddled around the scrapings, making sandwiches for all Toru’s family could tell.

After years of prodding, he was officially diagnosed as “very curious. Very curious, indeed.” Then the doctors took turns punching him in the stomach, marveling at how he didn’t bruise. Toru was four.

In those days, the Sun squeezed through the thick grey clouds as often as ever. One could tell day from night, even indoors.

Later, of course, there were no grey clouds. The Sun masqueraded as a fuzzy splotch and the moon as a grey blot blocking a circle of stars. Everyone who could afford it wore chemi-heat suits to keep their blood flowing. Everyone burrowed deep underground in search of thermal warmth. Everyone, that is, but Toru.

The cold didn’t concern him. It didn’t penetrate. He claimed nothing could.

When he was a boy, playground bullies would wing rocks at his head, just to see them explode against his skull. The stones didn’t leave a mark. Toru would run away, his sneakers sloughing off into scraps. Exasperated, Mom decided no more shoes. No more school. Toru didn’t mind, though. He never cut his feet or felt the ice. It was only when he met Zai, though, that he learned why.

“It’s because you’re so compact, Toru. Do you see? Who’s warmer? A person in an empty closet or a man in a closet with fifty friends?”

Toru understood. In her analogy, he was the packed closet. He wasn’t stupid, just dense.

Who’s got fifty friends, though?

#

The Sun convulsed fourteen years ago.

It was late summer. Toru and his family were in Perlmutter Park, that pathetic square of pavement and dead grass. Mom and Dad and Uncle Taonga cooked chicken skewers. They pretended it was a nice day. Toru played by himself, picking dry yellow dandelions and crumbling them. It hadn’t rained since July.

Toru stood with his back to the afternoon sun. He crushed a weed and was letting its dust fall when the Pulse came.

People who saw it said the Sun contracted and then shuddered out into fuzz, as if you tried to focus a camera on it and your hand slipped. Toru thought his eyes had gone funny.

When he turned around, everyone was trying to look at the Sun without looking. Mom wept. Dad stared for too long and saw spots until the cold took him a few years later. Uncle Taonga tried to call his ex-wife in Wellington, but all the phones had fallen silent.

That was the last year Toru remembered there being dandelions. It was also the final year that lasted 365 days. But what difference did it make? No one was celebrating his birthday.

#

By the time Toru reached thirteen, summer felt like winter and winter felt like a cudgel to the bridge of your nose. Plants stopped growing, except in labs. There was one silver lining, though. Toru no longer had to worry about other kids taunting him. All he had to do was go outside to have the whole world to himself.

When he was sixteen, the oceans finally froze through and cracked like the paint on a picnic table. Glaciers stuffed their faces. Toru also hit his growth spurt. He shot up five inches and gained eight hundred and fourteen pounds. He didn’t put that weight on. He put it in, trash-compactor style.

Tautoru wasn’t a giant ball of blubber, like some bellowing elephant seal. He was an average-looking three-ton barefoot guy in a triple wrapped world. Everyone wore an electric-anorak and Toru watched the breeze tickle the hairs on his arms. He watched the Sun disappear in the sky.

#

Scientists and schoolbooks said the Sun would burn white hot for billions of years, brilliant and blushing and glad to see you.

Very funny.

When it first began to dim, astronomers blamed the dark matter boogeyman. They were wrong. As it turned out, some bastard made the Sun cry.

Educated people thought they understood cosmology and nuclear reactions, and they did, more or less. They just assumed that because humanity hadn’t figured out how to break the laws of nature, that they were unbreakable. They weren’t, of course; that shouldn’t be so surprising. Toru broke many things advertised as unbreakable: toys, kitchen implements, suspension bridges, whatever.

What happened was, people hadn’t taken Ng’s Law of the Limits of Attraction into account. Dr. Ng proved that while Sol served as the center of our Solar System, comet X/2013 B1 was equally important.

Zai explained it to Toru this way, “If you’re a kid, right, what keeps you playing in the yard? Is it your mom keeping her eye on you from the middle of the lawn or the fence around the edge? Does your heart hold you together or your skin?”

It was both. Toru got it.

The why didn’t really matter to him; he just liked listening to Zai. He knew that soon the Sun would dissolve into the universe like a drop of blood in the bath. He could see it happening.

When everything became scarce, and the dirty hail fell hard once more and never again, that’s when the dread overwhelmed everyone. The constant knocking of death’s imminent arrival made everyone crazy. The very rich grabbed the very smart and the very strong and they pushed whatever they could against the door, clamoring, “Save us all.”

“Save only me.”

#

When Zai was young, it was easy to vanish in the dim Los Angeles haze. She frequently stole away from foster homes, avoiding the gaze of overburdened den mothers to find out how far the city went. Once, she made it all the way to Malibu before the waves stopped her.

Zai’s home-cut hair swirled around her face in what was left of the wind. She stepped back quickly in the sand, but the waves reached for her. The frigid water tickled the sand around her feet and made her think of long-limbed sea stars scavenging off Antarctica. How deliberately those creatures must move.

Zai was a bright-eyed girl and she quietly outwitted her peers from infancy on. Whether her parents recognized her brilliance or not is unknown. They abandoned her as an infant in the lobby of St. Vincent’s.

When she was five, Zai read textbooks and didn’t tell anyone. When she turned eight, she learned calculus off the Internet. At thirteen, still scrawny and snaggle-toothed, Zai finally had an idea she wanted to share. She wrote it up in a meticulously mimicked style and submitted it to the International Journal of Astronomy & Astrophysics. Her self-preservation instinct suggested she keep her name to herself, so she used Dr. Hamid Afshar’s instead. He was well past puberty and more likely to taken seriously.

Weeks later, Dr. Afshar was surprised to receive an enthusiastic acceptance call from the IJAA’s senior editor. Hamid protested he hadn’t written the paper, hadn’t heard of the project. When they sent him a copy, he read it twice. Then he tossed the discs collecting his now pointless data into the microwave. They burned a beautiful blue.

The Journal published the submission anonymously, in defiance of protocol. It had passed peer review with no objections and only one suicide.

The paper asserted that the Sun had lost a connection essential to its continuance. It would gradually diminish in intensity as the forces that held it together dissipated. Within five years, everything recognized as the Sun would simply cease to be.

For the first time, a theory set out what was happening incontrovertibly. People read Zai Ng’s Theory of the Limits of Attraction and cried.

#

Toru was sixteen during the Great Panic. When it started, he had a family. When it was past, he didn’t. Four billion people starved and froze and were murdered within six months. Everything of value was plundered, as if the world was a giant convenience store before a hurricane.

Because of the chaos, it took ten months for anyone to identify Zai as the author of the Limits of Attraction. When they found her, her survival became guaranteed, at least for five years. By fourteen she had the remains of whole university departments piled on her doorstep. “What do you need,” they groveled.

Zai answered, “I need Tautoru Kahakura.”

She’d read about him in a medical journal and wanted him nearby. America might have been chaos, but one can always find a guy like Toru. Zai told them to triangulate using a pair of seismographs.

When Toru asked why she sent for him, Zai said it was because of his ability to scavenge supplies in the cold. He could smash through ice with a vigor that’s hard to muster when you’re wearing mittens.

The other scientists thought Zai was softhearted, but she was sharper than tungsten flame. So they let her have Toru. There were no competing claims.

From the start, everyone saw that Toru loved Zai. Less clear was how Zai felt in return.

Their interactions fell into gentle patterns. Toru always came in slowly, minding where he swung his arms. Zai usually spun around in her chair, her legs dangling or tucked beneath her. There’d be a wisp of hair shifting in her eyes. She’d say something like, “Toru! I’m glad you’re back!” He’d blush and his voice would crack and he’d tell her what he’d brought her; steel, magnesium, sulfur, copper.

There were no more flowers.

Maybe Zai would beckon him closer with half-open eyes. Sometimes brilliant Dr. Ng would confide that her trials kept failing. He would tell her stories of what he’d seen outside. And then she’d always thank him. “Thank you so much, Toru. Can you…?”

“Yes. For you, Zai, I can.”

And still Toru grew. In Earth’s corner, in the black shorts, standing six foot two and weighing in at four thousand six hundred and seventy-three pounds: Tautoru Brick-oven Barefoot Sledge-finger Still-alive Kahakura. Too heavy to hold, too solid to cut, too tough to fail, too lucky to love. So very lucky.

In the shifty eclipse light of day, Toru walked alone.

#

Zai’s team launched another rocket. This attempt traveled at the speed of light only for the moment its contents–soft men and women–burst apart. It did not leave the ground except as ash. The scar it cut in the ice went jagged and deep. It filled with water for dancing seconds before it froze again, rippling.

Toru felt the blast of people’s lives flash against his bare face and he clutched his eyes tight, bracing himself for the shockwave. As the heat and light and humanity hurled against him, the ice creaked under the soles of his feet. Zai, wrapped tight in the control booth, watched the ash swirl in the disturbed air. She saw Toru try to brush it off his skin.

Hours later, Toru sought Zai out in her lab. Deep, deep down she sparkled, a tiny girl with dark eyes. His love for her stained his face.

“Zai, how did you know? About the Sun dying?”

She put down her instruments and glanced at Toru over her shoulder and through her hair. Her dark brows said, “busy,” but her eyelashes quietly disagreed, streaking across her glance like a meteor shower. Toru edged close, but not too.

“I saw the connection, Toru.”

Zai Ng, the world’s most revered scientist, sat up in her chair and hugged her knees to her chest. She twisted her body and the chair spun, fast at first then slow. She waited for the chair to finish its rotation before saying more.

“When the Sun first began to diffuse, everyone was crazy with guesses. What could make a yellow star just give up?”

Zai looked Toru in the eye and let a glint of her wayward smile escape. He looked away shyly, so she considerately redirected her gaze. “It was loss, Toru. Things, like people, give up when they run out. The Sun had plenty of hydrogen fuel, so it had to be lacking something else.

“I tried to discover what had gone missing; I was used to doing that.” For a moment, she paused and Toru watched an unknown weight steal her smile. When she continued, her voice sounded thicker, darker.

“I snuck away from where I’d been living. Squirmed into the university. Just by calculating, I found the answer. The Army had been testing laser weapons on comets, hunks of rock and metal and ice floating through the Oort cloud. They were inconsequential things, the comets, perfect for target practice. Not any big loss, according to the Army.”

Darkness wrinkled the smooth skin of Zai’s brow and settled in her jaw. Toru took a half step towards her and she looked up at him, startled from her burrow. Her resulting smile was so sweet it constricted Toru’s heart. He blushed and this broadened Zai’s grin. Again, she looked away before he felt the need.

Zai went on. “I plotted out the orbits of the destroyed comets and saw that one, a small one, had been doing a slow wiggle at the edge of the Solar System. This comet wasn’t even a target. It got hit by a beam that went wide.

“It hadn’t had a regular orbit, this comet, and that was strange. Normally comets travel in huge ellipses, maybe jogging near planets, but still; they’re predictable. This one though, every time you’d expect it to escape the Sun’s gravitational field, it would nudge back in. But how?

“Well I was looking into the dimming Sun, right? So I looked for a correlation. And that was it. Every mysterious shift in the orbit of that comet matched a solar flare, a Sunspot, or some other fluctuation in the Sun’s magnetic field.

“Each time I looked at the data, it became clearer that the Sun and this comet were connected. Just this particular one. I’m not positive why? A unique composition, perhaps.

“Anyway, after we destroyed it, all normal solar activity stopped. The Pulse.”

This made sense to Toru. Zai talked on, though, branching into physical cosmology and tensor calculus. When she glanced over, her face reddened as if a phantom parent had scolded her. She was a fool, making him struggle to keep up.

She tried more gently. “Picture a giant piece of string between the core of the Sun and this comet. This connection helped the Sun contain its mass so it didn’t leak out as dark matter. The string held the Sun together like a giant tied-off balloon. When X/2013 was destroyed–when we destroyed it–the string came untied.”

Zai looked Toru in the eyes again, just briefly. She didn’t want to spook him, but she wanted him to understand. Before he looked away she glimpsed his sorrow, so perhaps he knew.

“Sometimes, things are just clear to me,” she added. “Like there’s a spotlight on an answer that no one else can see.”

Zai picked up a tiny vial of powder, iridescent black and fine as pollen. She cautiously took Toru’s hand. His mitt, heavier than a stack of anvils, floated in her fingers. Zai carefully poured a few grains of dust onto the callused pads of Toru’s palm.

“This is one of those answers, Toru. I saw it almost immediately, but I hoped to find something less desperate. Now, even a terrible idea sounds pretty good.

“This is a kind of fuel,” she explained. “Very volatile. If it hurts you, I’m sorry. Okay?”

She stepped behind him, her cheek to his back, and reached around with a sparker. A glint leapt into the blackness and it was black no more. The iridescence snapped off the dust and bit Toru in the eyes. The dust sucked into his hand, and tiny tattoos shot the room. Then he heard it, a whisper-pop ear-scratching yolp followed by a creaking snap. The yolp was the dust exclaiming. The snap was the stone floor cracking underneath his feet.

Zai held close, trembling. He felt her cling to his back and he was afraid to exhale, to pull the shock from his ears or the tears from his eyes. He begged the moment to last. Then, tentatively, Zai unstuck herself and slid around. She looked up at him as he undid the fist of his face.

If she had asked, he would have said he understood. He thought the fuel was her brightness, a jump to light speed, but he was wrong.

Zai leaned close to Toru as the engineers came running. As they stormed in, she spoke so everyone could hear.

“I need you Toru. I need you and I need you to understand. Will you…”

Toru recognized his cue. “Yes. For you, Zai. I will.”

#

Toru was a plow. His tough shovel fingers scooped through ice to dredge the fertile depths of buried cities. Zai had sent him for materials to build a giant launch structure eighty miles out over what used to be the Pacific Ocean.

He easily pulled metal from the ruins but finding it grew trickier. It was left to Toru to tunnel inside ruins and search the walls for support beams. Inside was where people used to be, when they talked to one another.

Toru tunneled through businesses and apartments and hospitals. Sometimes, when he was not being careful, he tunneled through people. Everything encased in ice, it was easy to mistake an arm for a chair. Having wounds cleaved through them did not affect corpses’ expressions of dumb fatigue. It affected Toru’s. He tried not to think about it. He just took the steel that the buildings no longer needed. They stood solid with ice walls, ice air, ice people.

Toru considered the survivors. Scattered around the planet, a handful of well-defended catacombs supported tenacious communities: New Reykjavik, with its geothermal heat, for example, or nuclear-powered Pyongyang. People there might survive the death of the Sun for a while, if war or illness or the lack of nutrition didn’t do them in. Then there were the old school spaceships, slowly ferrying their stir-crazy passengers out past the gas giants. Zai said she could have hitched a ride or migrated somewhere more comfortable but she didn’t see the point.

“When will any of those people breathe fresh air, Toru? Without the Sun we might be able to keep ourselves alive, maybe even for years. But resources are already running out. People simply can’t survive for long without warmth. And I don’t want to.”

#

When Toru first saw the launch complex, he was confused. What Zai built did not resemble a rocket. It looked like a pyramid with a muzzle projecting from its apex like a short straw.

Toru watched as workers secured a thirty-foot thick capsule of steel into a hoist. His eyes tracked the hoists’ chains up towards the muzzle. That was the entire ship, he realized.

When Toru reached the throng, Zai called him over. She showed him the ship while the others hugged their arms tight to their chests. His tour didn’t take long. The capsule had one narrow shaft leading to a central cocoon filled with life support. There was only room for one. The launch structure was hollow but for a crawlway leading to the central ignition mechanism.

Workers scurried over the pyramid like head lice, filling it with sacks of black iridescent explosive. The capsule, the tube, the pyramid: the whole thing was a giant firecracker designed to shoot a metal pea towards a livelier star.

Toru tried to answer his own questions: How are they going to build a ship big enough to carry everyone? Can any fuel make something go faster than light? What will become of the test pilot?

That evening, he sought out Zai in the bunker. She was twirling a stylus in her hair and rocking slowly over a flat output screen.

Zai took a moment to turn. Toru took a step closer, carefully, but the ice floor moaned.

Toru heard himself say, “I volunteer, if you want.” Zai raised her eyes to him, but she didn’t look away, even when he did. Her eyes were tinged with skittish fear.

She stood, a hand against the desk for balance. Her head only came up to Toru’s chest. “You can’t, Toru. No.”

“You need me to get more metal. I can do that first. Even if this one doesn’t work right, if it blows up, it’s okay. I volunteer.” He remembered the stares, the stones exploding against his skull.

“It’s not that, Toru. It will work.” She sobbed, surprising him. The tears crackled from her half-covered cheeks like ruined chandeliers.

“They’re building a bigger ship now, near Cabo, big enough for hundreds. The design is a joke but they’ll never finish it anyway. This capsule will be the only one.” Her breath was serrated and raw. “You can’t take it, Toru,” she said, “because I want to.”

She started laughing-crying and Toru felt the frantic scratch of clawing chaos. Dr. Zai Ng fluttered close, fighting the draw of him. Her throat made a noise his couldn’t and then she let her forehead and hands fall onto his chest.

It was the most keenly edged moment of Toru’s life. Zai held him and said she was leaving. He wondered if being missed was the same as being loved.

As he leaned down to her, the black gloss of her hair lifted from her delicate face and caressed his skin, as if driven by static charge. Wisps of her bangs framed their faces. Through the strands, the faint laboratory light reflected the flash of Zai’s eyes. Even in anguish, they gleamed.

Zai’s slim neck relented as she joined Toru in an embrace, each moment of ease tugging them closer. Her arms took his neck and her feet hooked around his pylon thighs. He felt her tiny breasts against his chest and–remembering frozen faces tunneled through and the needle-pierced sky–Toru opened himself to her warmth.

Letting the wretched fortune of his density cling them together, Toru’s arms did not hold her. They only felt the limits of her. The edges of her skin graced the tips of his fingers. And Zai pressed her face into his neck, crying silent tears that tickled as they froze.

“You don’t know how important you’ve been to me and how important you are. But I’m going. I have to. I need to ask you…”

“Yes, Zai. For you, anything.”

She smiled and cried and kissed him. And nothing could have been more important to him, to her, or to anyone left alive.

#

When Toru was just a kid, there were dandelions. They’d start the summer bright and yellow and warm. Then, somehow, without you noticing it, they’d turn white and diffuse like the ghost of a hatchling, a ball of feathers with no bird. And then someone would pluck one, laughing because there were endless fields of them, and blow all those ephemeral bits to the wind.

As Toru watched, that’s what happened to the Sun.

There was no big throbbing explosion that shattered the ice or any all-consuming implosion that warped the stars. The Sun just drifted off. It dissipated into tendrils like a lungful of smoke.

The temperature dropped desperately while those caught outside watched. It kept plummeting. For the first time, Toru knew cold. No one would spare him a coat, even though he said he wouldn’t need it for long. Orange snow fell as the methane in the atmosphere crystalized.

An explosion slapped Toru’s face. Light and heat throbbed from the command center, now in flaming ruins. Concerned for Zai, it took Toru a moment to comprehend that someone was shooting at him. Three workers fell, deep red blood pushing from their wounds like toothpaste. The bullets scratched at Toru’s skin and left scorch marks.

Toru stared at his blue-tinged toes as the gunman scrambled up the pyramid’s stairs. Toru could hear the taunts. Mom would be disappointed. He’d ruined his shoes again.

Toru stood alone, desperate for a chance to change the way things were. “Things will get better,” he heard Mom lie sweetly.

Mom was dead, though. And that capsule Zai’s.

Toru jumped high and let himself fall hard. The crater his cannonball made in the ice threw shards for half a mile. The whole pyramid rattled and the gunman toppled off it like a pachinko ball. The way he landed, Toru doubted the man could survive, but then who would?

From the wreckage of the bunker, Zai Ng moved towards Toru as fast as she could under all her layers. She was still with him. Her need was real.

Toru escorted her to the launch structure, treasuring every step. This was his walk to the altar. He would never feel more like a groom.

When they reached the stairs, Zai climbed up a step and turned to lean her head against Toru’s. He could see her eyes through her frosted goggles. He was shy and afraid but he kept his gaze locked to hers.

Zai pulled a sparker from her pocket and put it in his hands. And then she touched his lips with her gloved fingers and hurried up the stairs.

Toru watched love leave his grasp, one step at a time.

Toru ran to the launch structure’s internal access panel, swamping himself to his hips in shattered ice. It was too late to step carefully. There was nothing left to ruin.

He hauled himself out of the frozen sea and pushed towards the crawlway. Toru took a final look up at the capsule as he heard the hatch seal, turning his back on the rest. Out loud, to no one at all, he said, “I guess this is goodbye.”

#

When Toru reached the tunnel’s end, there was nothing but a cube he could crouch in. It was a chamber underneath twenty-five million cubic feet of iridescent black fuel, a couple of sacks of which could knock loose the Moon.

As he tried the lifeless control panels, Toru wondered if the Earth still orbited the space left vacant by the Sun. He decided probably not. The dog was off its leash, running wild.

In the thin lighting, Toru found the fine chain dangling from the ceiling. When he tugged it, a small plug came free. Black powder started to mist into the chamber.

As it wafted around his knees, Toru thought of Zai in her capsule. He wanted to think about his Mom, to remember something tender, but nothing came. Time was up.

He raised the sparker and activated it. As he noted the miniscule flare that leapt from its tip, he thought, “I did that,” and then the world turned to energy around him.

He was, for the first time, brilliant–more brilliant than even Zai.

#

Hopefully Zai survived the explosion in her capsule. Certainly no one else within hundreds of miles did. The sea turned to steam down to its very depths, falling back as flash-frozen knives of rain. The Earth cracked as the cataclysm kicked the planet away. It loosed a tower of molten stone that cooled before it fell, a pillar to mark the place where Toru last saw Zai.

In the first taste of the blast, less than an instant, Toru finally understood what Zai had seen in him. The explosive pressure didn’t destroy him; it fed him. Each erg tore into Toru as he retreated into his solid core. His flesh eviscerated. His senses breached their channels. He became denser than diamond, denser than black, as dense as a star.

The explosion passed, but he remained. Pulling it all in, the starlight and interstellar debris and the cold. So dense of Toru not to have seen it, but there it was. So dense, so hot, so fierce with fear and need and love that he burned for Zai a nuclear fire. He sensed her hurtling away and reached out the fingers he used to have to stroke her jet-black hair. He found her streaking out towards the limits of his attraction and caught her, feeling something tug deep within as he struggled to keep her close. She was much farther out than the battered remains of the Earth, but he sensed her still, alone and in need. As he gloried in her pull, everything settled into a new orbit, not around him, but inside of her. In the sweep of their embrace the planets spun on.

And those that survived, they emerged from their desperately defended catacombs on Earth. They tried to see through the ash and turbulence, wondering what could possibly shine so brilliantly in the sky. Most, at least, were wise enough not to stare.

It didn’t matter, though. Toru was there regardless of them or their opinions. He only burned for Zai.

As long as she remained within his reach, he would caress the twisted and charred steel pod in which she slept. It might have resembled nothing more than cold, dumb metal, but Toru survived–as did everyone else–because of what that tarnished shell concealed.

Zack Kushner is a writer of stuff for those who wish to invest in pleasingly arranged letters. He has done that sort of thing for a long time. You can trust him. He is a professional. He also co-edits the cinema blog Stand By For Mind Control. He once chased a 20-foot long snake, hitched down the Vegas strip wearing only a barrel, and made Jamie Lee Curtis cry, but not all at the same time.