J.C. Reyes: “Paul Jean Paul’s ‘Reliable Write-In: The Making of Sitting Down‘”

He opened his door, and so I paid the price to get in. I wasn’t the only one. Critics from as far as Philadelphia scrambled to his doorstep and alternately filled Paul Jean Paul’s study as he embodied process, often without turning around or talking, sitting at his desk, his gaze lingering occasionally to his window, his backyard, demonstrating for everyone present the act and metaphysics of writing.

Jean Paul’s announcement that he’d be opening his study for inspection and critique wasn’t altogether surprising. The man had slowly been transforming the writing process into demonstration, something not unlike a drama. His previous novels, Juxtaposing Bourbon and Burgundy and Incognito in Río, were a creative test of and preparation for process as theater. During the creation of each book, he’d invited his neighbors, fashionable or not, intended audience or not, widow and child, alike, into his study. He’d asked them to make themselves at home. He’d offered them tea, coffee, and Danishes. He’d offered them bottomless buckets of peaches and cigarettes. And then, for all intents and purposes, he simply disappeared into the text.

As Jean Paul noted in an interview with the Dutchess New Ledger, “I don’t think my neighbors knew I’d invited them to watch me write, and I don’t think they knew how long I wanted them to stay. Some of them uncomfortably tried a conversation, but I didn’t reply. Some even repeated their ice breaking questions in lower tones, like whispers but mostly just inaudible. But I didn’t care about meeting their eyes again. I just wanted them to watch me write. It took them a while to catch on, if they caught on at all.”

And there’s conflicting evidence that his audience knew what was going on.

After the first unsurprisingly subdued spectacle, and two weeks after the last observer guest left Jean Paul’s house, the Newton Constitution Journal was the first to pick up the story. In their words, “A writer in America has opened curtains to matters of process and all those things that go into a written book, good and bad.” The newspaper’s opinions editor lived four doors down from the author, and he was literally the last person to leave Jean Paul’s study as the author completed Juxtaposing: “What he wanted from me, I still don’t get. It makes sense that exhibitionists need reluctant participants, but this: Jean Paul’s stunt has no historical precedence and so it has no term. What it might have is a conundrum definition: bored, brave, outcome unspecific, a staging without directions.”

For the following book’s staging, in the Holmes-Rockford Times, book critic Gayle Hass lambasted the author for succumbing to celebrity: “First, he charges readers for his presence at dinner, which witnesses have called ‘a hollow conversation with a white noise maker.’ Next, he uses corporate sponsorship from companies specializing in specialty pens and specialty watches and specialty bookmarks. And now this: a fool’s errand to significance. If his last collection of stories is any testament, the man is irrelevant, and he is probably the last to catch on.”

What was my take?

Perhaps Jean Paul, in his first two attempts, hadn’t refined the process of modeling the process of writing. Or perhaps he hadn’t quite fully envisioned the complete or idealized process to model. No matter the case, the presenter and presentation I was privy to on October 17th, as Jean Paul began Chapter 4 of his eleventh novel, tentatively entitled Sitting Down, was a tasteful critique and hearty reflection of form.

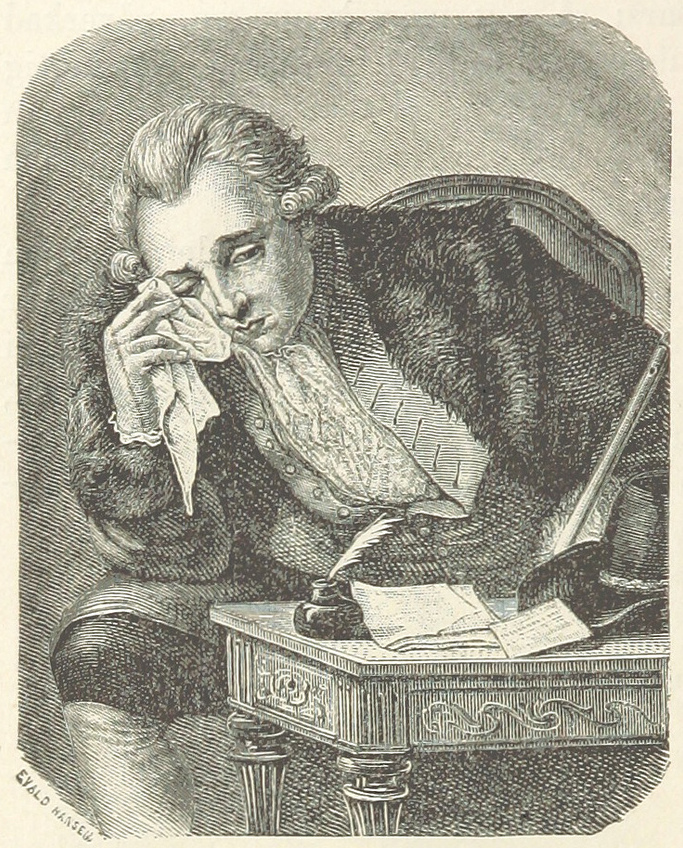

When I first walked into his study, I saw his audience lining the back wall in two rows. We were critics and readers and neighbors. Critics noting Jean Paul’s minutes-long preoccupation with single sentences and the choices he cycled through to replace a single verb. Readers in glasses and short-cropped hair smothering the rest of us in cigarettes and leaning over Jean Paul’s shoulder from afar to note names and decisions and page numbers. Neighbors whispering about Jean Paul’s pensive claps and rubs, the flicking pen that sometimes interrupted the correct punctuation or whatever Jean Paul too often passed for correct punctuation. There were sighs between us, though no one feigned even the slightest exhaustion or impatience. We all watched the man type, even if sometimes too slowly to measure in seconds, even if other times too fast we found ourselves gasping when he finished his sprint. One too many of us suppressed coughs so as not to interrupt—or merely feel like we could possibly interrupt—Jean Paul’s progress-in-progress, the art of making art in the making.

The first notable act of procedure came at approximately 9:15 a.m., when after well over an hour sifting through what he’d previously written and adding to that in uneven gradations, scrolling up and down several pages, copying and pasting and then editing and revising, Jean Paul stood up and began pacing circles. The room’s collective anticipation erased the air, and my brain was no exception to the cardinal rule: that when someone else’s sudden motion freezes you, you can only picture the beginning of said motion and so you judge that its end must be imminent and soon. And so I couldn’t immediately discern what Jean Paul’s first steps led into, until he began something of a straight line. It was only after one arc became consecutive arcs and they became the rumblings of a complete revolution that any of us realized that what the man really needed was to think.

As he circled near us, the first row of observers inched back into the second to make room, and the second row (myself included) thumped into the bookshelf behind us, rattling a recent re-edition of Haverford’s Playing Fiction, Playing Gods, which I kept from tipping over, and whose collapse would have embodied the attentive silence I’d succumbed—we’d succumbed—to and whose reflection I can only put into words now: that perhaps the novel had suddenly turned on Jean Paul and what he needed most in the world, to recapture himself and his audience, was to circumvent the story’s shift before returning to center.

Imagine the theatrical equivalent: a lead actor pauses midline to breathe, to understand the next complete expression or exasperation. Imagine an athletic one: a shooting guard pauses midstride to feel the meter in his hands, to bend and then stop time before taking his shot.

Jean Paul’s second act of procedure arrived at approximately 9:45 a.m., when he leaned back in his chair, cracked his neck, reached into his drawer, pulled a cigarette from his flip case. He lit it. We watched him. His chest rose. It fell. His feet swayed. His eyes lost in the portrait of a well-worn door above his desk. We watched him so completely that if he’d allowed everyone to stay the full day, he would have inadvertently guided our exhales into circadian rhythm, certainly a human first but, most importantly, a literary first. The flip-side of this, though, was as unmistakable as it was daunting: if his novel was going to be any good, it would have to learn reflect its very making, this experience: Sitting Down would have to capture precisely this posture and momentary misdirection for Jean Paul’s reader, for me, for us all in the room in that experience with him, because, otherwise, the novel would fall by way of middle-of-the-road movies: a distant second to the experience of reading the original book.

Had Jean Paul known, as he pressed his lips into the butt of his cigarette, that we breathed his second-hand smoke at the same rate he let it billow above us, I think he would have understood the complicated nature of the game we were all playing: that there was no referee, that we trusted him to police himself, to keep himself in bounds, knowing full well the nature of this game required, in order to remain sustainable straight through to completion, a self-awareness on par with, but without the destructive capacities of, an underground man; that Jean Paul had to follow his own rules for this to work, and he had to notify us, through silence and mental calculation, when and how those rules were going to change.

At approximately 10:25 a.m., I thought I recognized one such remove. He’d sighed and pushed his keyboard aside. His left hand for a spell seemed lost, his fingers tapping the wood lightly and reaching for all directions at once until he found a pen and then quickly reached for a brown notebook. He opened to the eighth and then ninth page, flipping slowly through the first many sheets as if photographing mind maps in no particular arrangement. He held his pen to write and then almost immediately held it to point nowhere. He stopped. The rules he’d set up for us, for himself, had almost broken down completely. What I had interpreted those rules to suggest were nothing short of unyielding consistency: that he was not going to embody, whole or in part, even the illusion to stop.

That he would pause, sure. That he could pace his room, absolutely. But that he’d mime a gesture alluding to a complete stop was not in the contract, however intangible the purpose of even these theatrics were.

I think he knew that. I’ll give him the benefit of the doubt that reviewers before me, of his previous dramas, did not. Because as soon as I started paying attention again to the smell, an indication I’d been pushed too far outside the bounds of the space he’d created inside this room, Jean Paul reached into his drawer again, smoothly. He rifled softly through pens and a stack of loose sheets. When he finally pulled out someone else’s book, a novella of sorts—it seemed, in any case, a thin book—he opened it. He leaned back, settled the book on his lap. He started reading. The many of us against the back wall breathed again. We got lost in the diagram of Jean Paul’s hand pulling the cigarette close and then ashing it on the floor and then his hands together turning the page.

J. C. Reyes is originally from Guayaquil, Ecuador. His stories, poems and essays have appeared in Arcadia Magazine, The Brooklyner, and Hawai’i Review, among others. He received his MFA from The University of Alabama, where he currently teaches creative writing, literature, and composition.